Posted: April 20, 2022

LF is currently found in 45 counties in Pennsylvania, all of which are under a state-imposed quarantine.

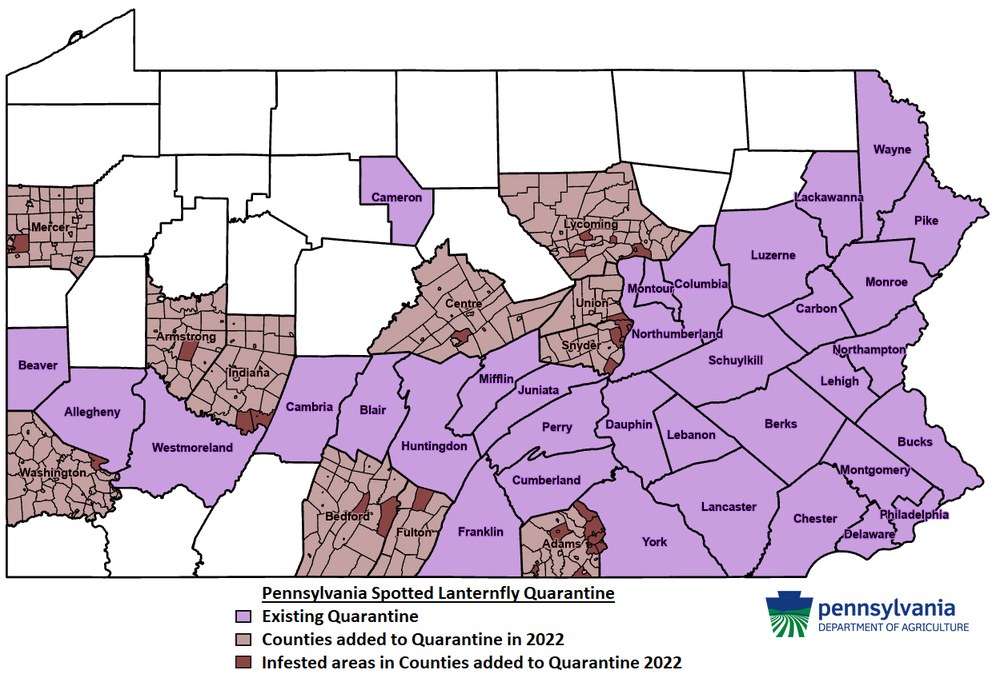

Updated map of Pennsylvania showing the counties currently under spotted lanternfly quarantine

Sunny skies and rising temperatures have many on cloud nine with anticipation of summertime fun. But for residents in parts of Pennsylvania and beyond, these weather conditions also signal the return of a trespasser that aims to rain on their parade—the spotted lanternfly.

The pest, which feeds on the sap of grapevines, hardwoods, and ornamentals, strikes a double blow—not only does it stress host plants, but it also can render outdoor areas unusable by leaving behind a sugary excrement called honeydew, explained Emelie Swackhamer, a horticulture educator with Penn State Extension.

“Egg-hatching season is here, and that has some people on edge,” said Swackhamer, who added that the pest now has been reported in 45 Pennsylvania counties. “The spotted lanternfly is an insect that takes time, energy, and money to keep under control, especially in heavily infested areas. Those dealing with this pest for the first time likely will be frustrated, but arming oneself with knowledge can help.”

The nonnative spotted lanternfly (SLF) completes its life cycle in one year. It grows from egg to adult in three stages, with its appearance changing during the molting process for each stage, noted Amy Korman, an extension educator based in Northampton County.

Hatching lanternflies are initially white and can be observed from late April until June, depending on environmental conditions. Their exoskeleton hardens, quickly becoming black with white spots.

As they enter their “teenage” days, the insect’s primary color is red instead of black. By midsummer, the nymphs will become adults, measuring about an inch in length and sporting artfully patterned wings of red, black, white, and tan, accented by dots. During this last phase of their development as the last nymphal stage molts, Korman pointed out, the newly-emerged adults look odd, exhibiting a disfigured appearance.

“Their wings are soft and folded and not the typical colorful patterns that we see on adults,” she said. “However, they are normal lanternflies entering the last phase of their lives. Once the insect emerges from its old skin, it expands its size, and additional physiological processes will cause the insect skin to harden and darken.”

Throughout the transformation, one thing remains constant—the lanternfly’s voracious appetite, and that has citizens looking for ways to control the clusters that have taken up residence on their properties. The educators offer the following management tips based on the pest’s life cycle:

Destroy egg masses—fall, winter, and spring

Check for egg masses—gray-colored, flat clusters—on trees, cement blocks, rocks and any other hard surface. If egg masses are found, scrape them off using a plastic card or putty knife, and then place the masses into a bag or container with rubbing alcohol. The egg masses also can be smashed or burned.

Circle traps—spring and summer

Trapping is a mechanical control method that does not use insecticides. While traps can capture a significant number of spotted lanternflies on individual trees, they do not prevent lanternflies from moving around in a landscape and returning.

When the nymphs first hatch, they will walk up the trunks of trees to feed on the softer, new growth of the plant. People can take advantage of this behavior by installing a funnel-style trap, called a “circle trap,” which wraps around the trunks of trees. Spotted lanternflies are guided into a container at the top of the funnel as they move upward.

Circle traps can be purchased commercially or can be a do-it-yourself project. A detailed guide on how to build a trap can be found on the Penn State Extension website at “How to Build a New Style Spotted Lanternfly Circle Trap.”

Sticky bands are another method that has been used. Sticky bands have a major drawback: the sticky material can capture other insects and animals, including birds, small mammals, pollinators such as bees and butterflies, and more. To reduce the possibility of bycatch, a wildlife barrier of vinyl window screening or other protective material must be installed. Sticky bands deployed without a wildlife barrier are not recommended.

Removal of tree-of-heaven—spring and summer

While the spotted lanternfly will feast on a variety of plant species, it has a fondness for Ailanthus altissima, or tree-of-heaven, an invasive plant that is common in fencerows and unmanaged woods, along the sides of roads, and in residential areas. For this reason, there is a current push from spotted lanternfly officials to remove this tree. The best way to do this is to apply an herbicide to the tree using the hack-and-squirt method—a critical step to prevent regrowth—and then cutting it down after it is dead from July to September.

Use of insecticides—spring, summer, and fall

When dealing with large populations of the insect, citizens may have little recourse other than using chemical control. When applied properly, insecticides can be an effective and safe way to reduce lanternfly populations.

Penn State Extension is researching which insecticides are best for controlling the pest; preliminary results show that those with the active ingredients dinotefuran, carbaryl, bifenthrin and natural pyrethrins are among the most effective.

However, there are safety, environmental, and sometimes regulatory concerns that accompany the use of insecticides, so homeowners should do research, weigh the pros and cons, and seek professional advice if needed.

Swackhamer also warned against the use of home remedies, such as cleaning and other household supplies, as they can be unsafe for humans, pets, wildlife, and plants.

Slow the spread

SLF is currently found in 45 counties in Pennsylvania, all of which are under a state-imposed quarantine (see map). The quarantine is in place to stop the movement of SLF to new areas within or out of the current quarantine zone and to slow its spread within the quarantine. The quarantine affects vehicles and other conveyances, plant, wood, and stone products, and outdoor household items.

In addition to Pennsylvania, SLF is also found in New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Connecticut, Maryland, Delaware, Virginia, and West Virginia. Do your part to slow the spread by complying with the SLF quarantine regulations.

More information about the spotted lanternfly’s life cycle, management techniques, and quarantine regulations is available at the Penn State Extension SLF website: https://extension.psu.edu/spotted-lanternfly.

Adapted from an article by Amy Duke, Public Relations Specialist, Penn State

James C. Finley Center for Private Forests

Address

416 Forest Resources BuildingUniversity Park, PA 16802

- Email PrivateForests@psu.edu

- Office 814-863-0401

- Fax 814-865-6275

James C. Finley Center for Private Forests

Address

416 Forest Resources BuildingUniversity Park, PA 16802

- Email PrivateForests@psu.edu

- Office 814-863-0401

- Fax 814-865-6275