Article and photos by Jon Taylor recounting his experience taking part in the AT Mega-Transect chestnut count in the 2012 hiking season.

View from Little Hump Mountain, NC and TN state line

Jon Taylor has been a volunteer for TACF for about ten years and is currently on the Carolinas Chapter Board. He is a professional woodworker who enjoys the history of the chestnut lumber he finds. Already this spring, Jon has completed the 262 mile trek from Watauga Dam to Fontana Dam that he set out to hike last summer. He hopes hike to Springer Mountain, GA this year.

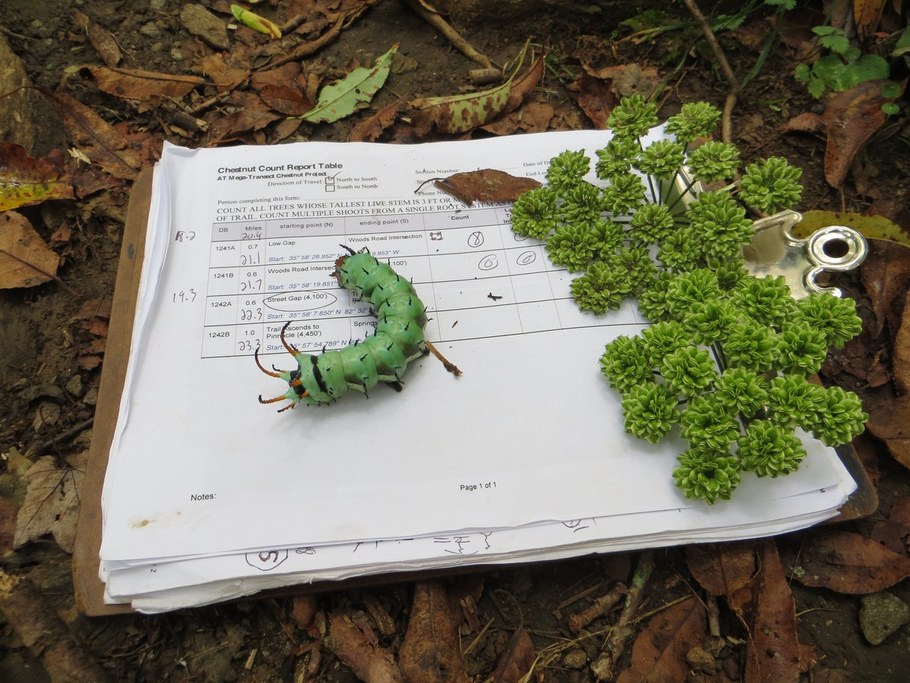

A few years ago I attended a presentation on the Appalachian Trail (AT) MEGA-Transect Chestnut Project given by John Scrivani of the Virginia Chapter of TACF. Volunteers select a section of the AT they would like to hike and count American chestnuts along the trail. John's presentation explained how the counts of American chestnuts along the entire 2,184 mile corridor of the AT are extrapolated to the original range of the tree to give a rough estimate of the number of survivors.

I don't recall the exact estimate but I do remember being amazed that there were still millions of saplings out there surviving in the understory. The population density in each section can then be compared for possible reintroduction sites. The project also collects detailed information on large trees for the possibility to collect genetic material to be incorporated into TACF's breeding program.

Last spring I noticed an announcement that Hill Craddock, Professor of Biology and Environmental Sciences at University of Tennessee at Chattanooga and TACF Board member, was leading a training session for the MEGA-Transect Project in Western North Carolina. Now, I already knew how to identify an American chestnut and all the regulations on the data collection, but I also knew that Hill's enthusiasm would be just the motivation I would need to begin my hikes!

The very next day after the training session, I was looking at a map of the AT. I noticed that the trail made a large half circle around my hometown of Asheville, NC. I decided to hike from North to South from Watauga Dam in East Tennessee to Fontana Dam in Western North Carolina. At a distance of 262 miles, I knew I couldn't do it all in a summer of weekend section hikes, but it seemed like a good goal for the next few years.

A few weeks later I received an email from Paul Sisco of the Carolinas Chapter of TACF asking if I could spend a Saturday helping to inoculate one of our North Carolina breeding orchards. I was excited for this opportunity, which would be my first experience with inoculations, but even more excited to realize that the orchard was just over the state line from Watauga Lake. We agreed that I'd help him in the orchard and he'd help me shuttle my truck to the end of my first section hike. It all seemed so appropriate. Paul's knowledge, hard work, and dedication to our mission have been an inspiration to me and have kept me involved with this Foundation over the years. That first hike was only 13 miles, but I counted 351 American chestnut trees and 2 "large trees" with circumferences of 13 inches and 29 inches.

The second trip began with a steep ascent of White Rocks Mountain in East Tennessee. Climbing a steep ridge, I heard a noise behind me and turned around just as a black bear crossed the trail where I had just walked. This was the first bear I had ever seen in the wild and I was grateful because I always imagined seeing my first one from a car. The bear reacted the same way that almost every other hiker I've met told me it would by running the opposite direction into the woods.

The third trip included the scenic highlight of the entire summer: the Roan Highlands, which includes about fourteen miles of the AT above 5000'. This section passes over several beautiful balds and the spruce- and fir-covered summit of Roan Mountain. This forest type is a remnant of the last ice age and is only found on the highest peaks of the Southern Appalachians.

The next trip included a memorable campsite at the appropriately named Beauty Spot. There I met a large group of college students who were car camping for the weekend. They obviously felt bad that I had been hiking all day and offered me a beer. When I told them my dinner was beef jerky and trail mix they asked me to stay for a dinner of grilled vegetables and hamburgers. In all honesty, I felt bad for them too. That weekend I saw over twenty miles of some of the most beautiful mountain scenery in the world and all they saw was the 300 foot trail from the parking lot to the campsite.

The evening ended with a beautiful sunset. The next morning I came upon an area that had recently burned. The steep, south facing slope was covered with chinquapins and American chestnuts. Almost all of them had burs on them due to the open canopy and high light exposure.

My first trip of September crossed the open, grassy summit of Big Bald Mountain. The AT guidebook described the panoramic view as one of the best in the southern Appalachians. Unfortunately, I reached the summit mid-morning in a dense fog. As the forested ridge opened up into a grassy meadow I saw a group of people sitting at tables under a tent canopy. As I approached, I realized they were banding songbirds. The mountain is visited by many species on their north to south migrations. The volunteers had an amazingly efficient system where each group of two would take a different measurement or observation so each bird quickly traveled around the table and was then released into the brush. Another group of researchers uses the mountain to study raptors later in the fall. I hope to return this year to volunteer and maybe have a better view.

The next hike passed by a Civil War gravesite. Early in the war, David Shelton and his nephew, William, left their farm to enlist in the Union army. Returning home over Coldspring Mountain, they were ambushed and killed by Confederate soldiers.

A few miles passed the graves I reached the crest of a hill and down in the gap directly in front of me was a large male black bear. I was able to watch him for a few minutes before he became aware of me and slowly walked into the woods. It was near dark and I had planned on staying in the next shelter, which I thought was a few miles away. The shelter was right around the next bend so I anticipated seeing the bear again during the night.

The shelter had bear cables to suspend any food which deter bears from visiting. The young couple that was already at the shelter was a little uneasy about my story but the only thing we heard that night was the call of a barred owl.

On the last hike of the summer I was joined by my wife, Mandy. This section of the trail ends in the town of Hot Springs, NC. We had the choice of doing two easy days with camping or one 15-mile day and a relaxing stay in town. We chose the long day and didn't regret it.

In those seven weekend trips I was able to hike 153.7 miles of the Appalachian Trail. I counted a total of 3,299 American chestnuts and 15 "large trees" with a circumference of 13 inches or greater. Where most of these trees were growing is not new information to those who know the chestnuts' preferred habitat. The majority were growing on dry slopes and ridges, facing any direction except north. The main criteria seemed to be light exposure. The larger trees were almost always in an area where the canopy had been opened by fire, a fallen tree, or human disturbance. The trees in heavily shaded areas were stunted but surviving. I was even surprised a few times to find a chestnut tree growing in the middle of a dense stand of rhododendrons. What I was not expecting was the large variation in frequency from section to section. I would hike for miles without seeing a single chestnut and then as soon as the trail turned sharply at a stream, or crossed a ridge, there would be a lot of them. I guess I had never noticed how the rugged terrain of the Appalachian Mountains creates such a wide variety of habitats, which partially explains the large amount of plant and animal diversity.

Getting involved with the AT MEGA-Transect project has been extremely rewarding for me. Over the years I've found myself increasingly distant from the natural world. Being out on the trail has strengthened that connection and all the while contributed a small part to the worthy effort to restore the American chestnut.

-Article published in The American Chestnut Foundation's newsletter of June 17, 2013. Reprinted here with permission.